- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- Belle Vue – search archives catalogue

- Digital Resources

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

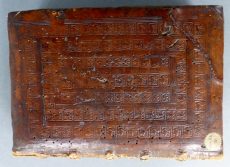

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

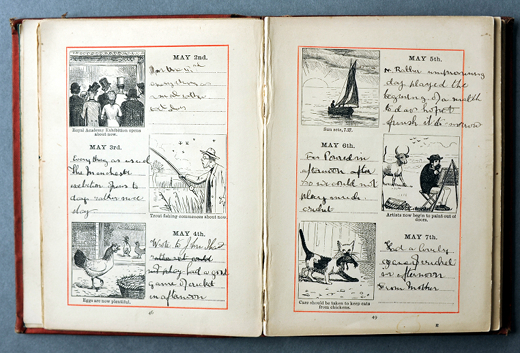

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Prints and Photographs

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Blog

- Support us

Diaries and Life Writing

One of the Library’s special strengths is life writing: those documents which record a person’s experiences, memories, and feelings. Life writing encompasses a large number of genres and practices – letters, autobiographies, biographies, personal essays, memoirs, and now takes in such new social media forms as blogs and Facebook.

Whilst the Library has large numbers of items from all of these genres, perhaps the most significant form in terms of our holdings is the diary. Indeed, we have some of the most important and useful personal sources for the history of the north west of England. A number of our early diaries, such as the diary for 1661-1663 of Henry Newcome, first minister of Cross Street Chapel, were among the very first publications of the Chetham Society following its foundation in the 1840s, clear recognition of the importance of the personal diary or journal as a source for the social, political and religious history of the region. Since the publication of Newcome, the Society has also brought out editions of other diaries in the collection of Chetham’s Library, such as the diary of Richard Kay (1716-51), a Lancashire doctor, and the diary of Edward Watkin, a pioneer of the railway industry in the C19th.

The task of editing and publishing extracts from diaries has been extended at the Library with the help of undergraduate history students from MMU, who have transcribed and published extracts from the collection of over two hundred diaries produced by four generations of the Leech family of Manchester. This is one of the largest collections of diaries ever produced by a single family, beginning with a childhood journal from 1815 and ending with a series of journals and notebooks from the early twenty-first century.

The majority of diaries at the Library, however, exist only in manuscript and although there is little possibility that many will ever be edited and published, a large number of them would repay further study. Of these we could mention an anonymous diary of someone who went with the Earl of Sandwich on his extraordinary embassy to Spain in 1666, which contains an early account of the fire of London, two volumes of religious meditations written by Ann Bathurst at the beginning of the eighteenth century, probably the longest sustained piece of mystical writing by a women in England, or the diary of Dora Turnor, a sickly teenager who documented her privileged life in Lincolnshire and in Belgravia in the 1870s. We also hold the early eighteenth-century diary of Methodist martyr William Seward, which has been digitised and made available as a pdf on our Digital Resources page.

In recent months the Library has acquired the diary of John Reed (1929-2012), which is the largest piece of life writing that we have seen. Reed began keeping a diary as a ten-year-old boy at the outset of World War Two, and kept this going throughout his life as an undergraduate at Oxford, his work in 1960s Rhodesia and his British Council work in Japan before his settling in Victoria Park Manchester. Reed’s diary runs to several hundred volumes, and he managed to write almost two pages of A4 every day of his adult life.

There are many reasons why diaries are of interest, but perhaps the most important is their private nature: because they were often not intended to be read by others they have have a open, candid quality that is hard to find in other literary forms. Edmund Harrold’s early eighteenth-century diary, for example, is well known for its record of the writer’s sex life, his bouts of drunkenness and his often comically fumbling attempts at courtship, but there are many other examples in the Library that are less shocking but no less entertaining than Harrold’s journal.