- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- Belle Vue – search archives catalogue

- Digital Resources

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Prints and Photographs

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Blog

- Support us

Seventeenth Century Crowdfunding with Knyff and Kip

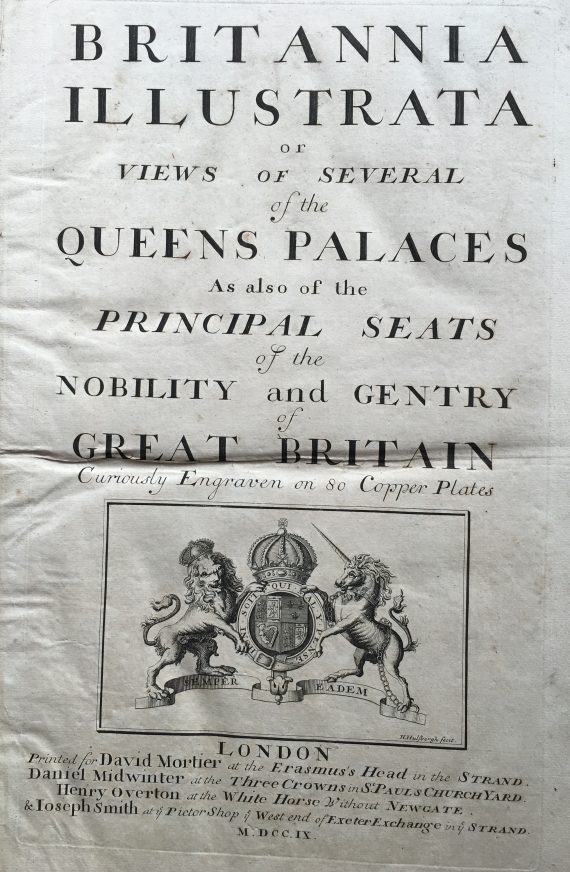

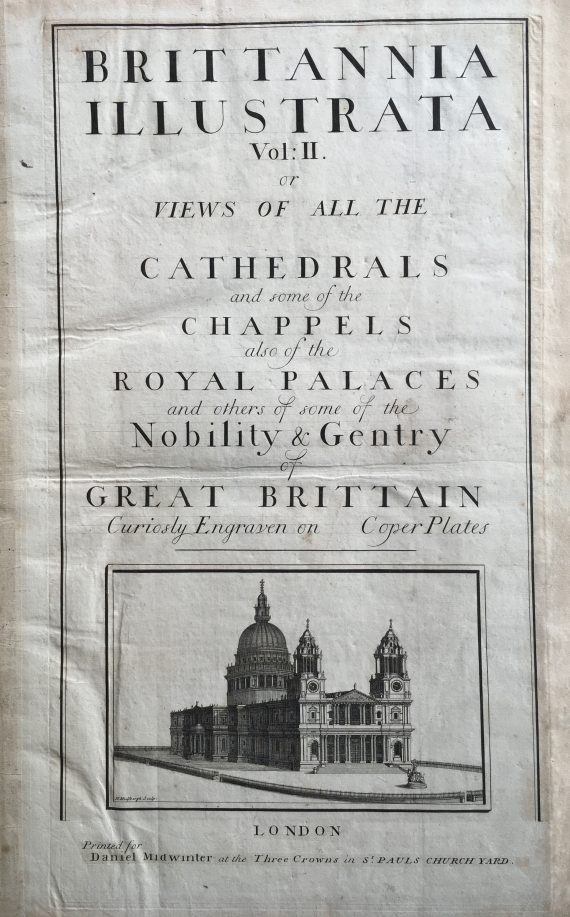

‘Knyff and Kip’ sound like a nineteenth-century vaudeville act, but were actually artists and engravers from the Netherlands, born in the mid-seventeenth century. Leendert Knyff and Johannes Kip were responsible for the publication, in 1707, of Britannia Illustrata, an extraordinary collection of engraved ‘birds-eye views’ of English country houses and estates. The Library has a splendid copy of a 1709 edition of Volume One and Two, somewhat chaotic volumes, both describing themselves as Volume Two.

Both Knyff and Kip travelled to England looking for work in the 1680s. Knyff was from a family of painters and initially specialised in still life but, no doubt in an attempt to attract more commissions, expanded his repertoire to include portraits, animal pieces and topographical landscapes. Kip was an exceptionally skilled engraver who trained in Amsterdam and arrived in England in 1689.

In the late 1690s Knyff came up with a cunning plan for a ‘subscription publishing project’ which he must have thought would be a financial winner. His idea was to play to the vanity of the British aristocracy, and produce a set of images of English country estates, funding the scheme by signing up the landowners in advance. For his £10 subscription each gentleman would have his house and grounds engraved including his coat of arms as part of the design and ultimately a full set of all the other prints. It was, essentially, a sort of early crowdfunding project…

Knyff seems to have approached prospective landowners, and begun making drawings and working with Kip at this point, but take-up must have been slower than he had hoped, for in May 1701 he was still advertising in the Post Man, for sponsors, declaring that he had ‘undertaken by way of Subscription, the Drawing and Printing of 100 Noblemen and Gentlemens Seats, whereof 60 are finished, and the Subscription not being full, This is to give notice to all Lords and Gentlemen who have a mind to be concern’d, to come or send to the said Undertakers house in the corner of the Old Palace-yard, Westminster; next door to the steps that go up to the House of Lords. The Articles are: that a 100 subscribers shall pay £10 each. That every Subscriber shall have two prints of each impression, which makes in all 200, and shall have 60 prints double delivered.’

Unfortunately, despite his best efforts, things didn’t improve, and by February 1707 Knyff declared in the Daily Courant that ‘for want of Subscriptions, and on account of his Health, (the time first proposed being long since expir’d) [he] is oblig’d to desist’. Knyff had also been dealing in prints and paintings for some years but clearly his financial problems were overwhelming and at this point he auctioned off all his stock, presumably including the engravings for Britannia Illustrata, and left England.

Despite this, later that year, a collection of 80 of the completed plates on single sheets was published by David Mortier (‘Book-Seller at ye Sign of Erasmus’s head near Bedford house, all sorts of French and Latin Books’). Mortier also published a second edition in 1708 under the title Nouveau theatre de la Grande Bretagne: ou Description exacte des palais de la reine, et des maisons les plus considerables des seigneurs & des gentilhommes … etc

The publishing history of Britannia Illustrata became increasingly complicated. Copyright on artists’ work in the early eighteenth century was very fluid and it seems likely that Kip, like Knyff, had actually sold his interest in the original work before it was first published. Mortier and other printsellers bought shares in the first collection of engravings and then added others to produce various different versions and eventually also a second volume.

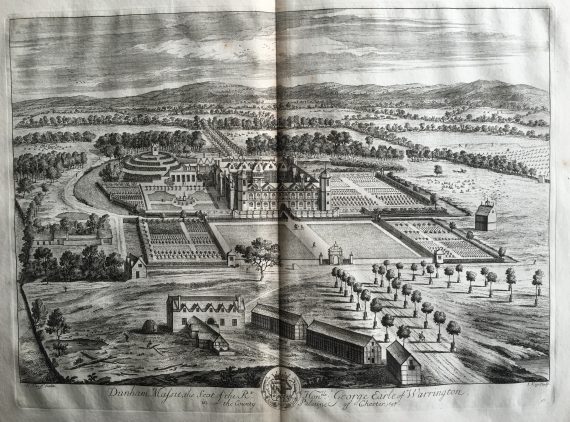

Reflecting this, the library’s copy of Britannia Illustrata (Volume 1) was published in 1709 by Mortier and three other printsellers (Daniel Midwinter, Henry Overton and Joseph Smith). The prints are fairly uniform in style and size and are almost all drawn by Knyff and engraved by Kip.

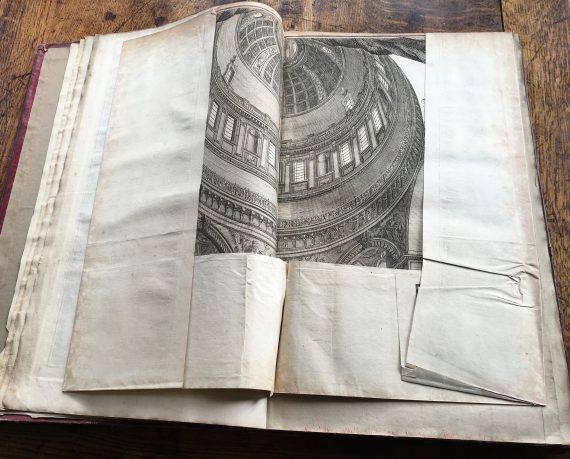

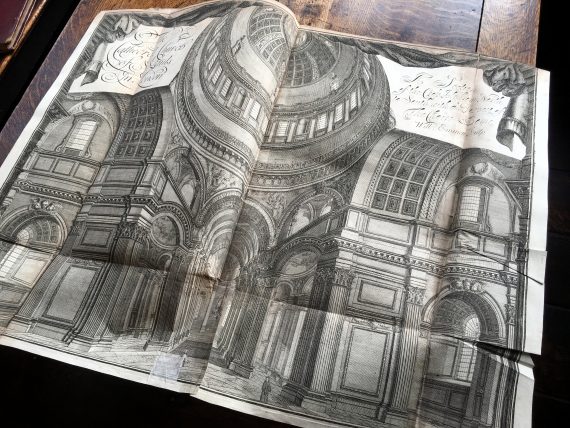

However, our two copies of Volume Two are quite different. One was published by Joseph Smith in 1716, which is mostly, but not exclusively, plates both drawn and engraved by Kip of more country seats. The other was published by Daniel Midwinter in 171? and is a mixture of different sized prints, some so large they have been folded, by both named and unnamed artists and engravers. This volume depicts mainly cathedrals and chapels, but also Oxford colleges and a few random country seats and ‘prospects’. The two editions share several identical prints.

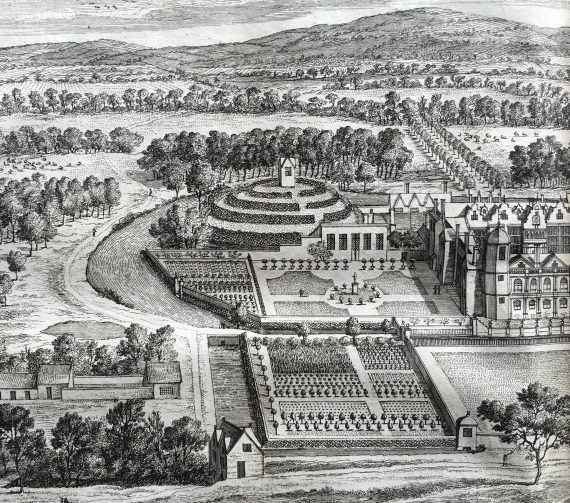

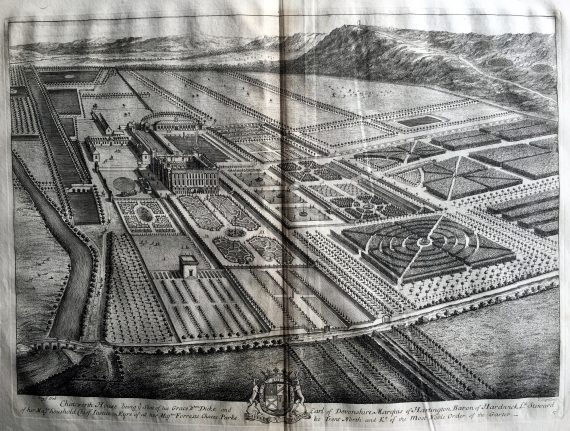

The most distinctive feature of Britannia Illustrata is that the images of the various houses are all undertaken as ‘birds-eye views’, as if Kip and Knyff had been able to fly above the properties in a balloon and sketch them. The perspective was actually achieved by using mapping and surveying techniques but it gives a very impressive view, which was undoubtedly popular with owners, because it clearly illustrated the full extent of their property, associated buildings, gardens and land.

A print was a cheaper option than commissioning an artist to produce an oil painting but still provided an excellent opportunity to impress others which was surely an attraction. Multiple copies were available, which could be folded or rolled for easy transportation or framed and displayed in other properties. Once the images were gathered together in book form, comparisons between the various estates became even easier and may well have generated feelings of envy or a determination to modernise or make improvements.

Amongst the images in the Library’s Volume One is a print of particular local interest featuring Dunham Massey Hall, our nearest National Trust property, and is the only print in the entire volume which includes a date as part of the engraving. The date is 1697, which is very early, and suggests that it could possibly have been the very first plate that Knyff and Kip designed for the project.

The print has particular significance in relation to the history of Dunham Massey. George Booth, the 2nd Earl of Warrington, had inherited Dunham (and the title) only three years earlier, in 1694. The house was in a truly terrible state, as his father, Henry Booth, the 1st Earl, had virtually bankrupted himself with years of political campaigning. The sight of his father weeping ‘from the greatness of his debts’ and of his mother borrowing from the servants seems to have haunted George for ever. When he inherited he became totally focussed on restoring the family fortunes, the house and the estate. The timing of the Britannia Illustrata engraving of Dunham is very interesting because in 1697 George had only just begun his work on the house and estate. Another curious fact is that, apparently at exactly the same time, the painter Adriaen van Diest made an oil painting of Dunham Massey which is also a birds-eye view. However, although the two images are very similar they are not identical. There is a long, straight, tree lined avenue running from the North (back) of the house towards a distant obelisk on Knyff’s drawing which does not appear on the van Diest painting.

One of the most significant projects which the 2nd Earl undertook was planting 100,000 trees across the park (partly with a view to making money from timber sales). Many of the trees still exist today. Is it possible that the trees on this Northern avenue were planted after Van Diest had made his drawings but before Knyff made his? If so there must have been a degree of artistic licence as the trees look pretty much full grown! It seems rather curious that George Booth should have wanted images of the house and estate before he undertook his programme of improvements, but perhaps that was exactly the point, he wanted a record of how the house and park had looked before and after?

This theory could seem to be supported by the fact that, half a century later, in 1751, after he had completed all the work on Dunham, George commissioned an artist called John Harris to make four very large and spectacular ‘birds-eye view’ paintings of the estate from four different directions. By this time ‘birds eye views’ were seen as very old fashioned but clearly for the 2nd Earl it was important to be able to make an exact comparison with the earlier images and demonstrate to his family, friends and future generations just what he had achieved.

9 Comments

Martin Rose

Fascinating, thank you. Can you tell me what “double-delivered” means exactly? The sentence “every Subscriber shall have two prints of each impression, which makes in all 200, and shall have 60 prints double delivered” doesn’t make sense if “double-delivered” means two prints of each impression; sodoes it actually mean something else?

ferguswilde

Dear Martin, a good question that deserves a good answer; I’m afraid we don’t have one! As you say, it must mean something other than ‘you get two prints of each’, because we know that. What is intended, I can’t guess – would anyone care to answer better, or speculate?

Peter Corry

I have copies of 2 of the Knyff and Kip views, and this is very useful background. For Londesborough and Kirkleatham, both of the “big houses” are long gone, but the more humble almshouses pictured in the surrounding estates are still providing accommodation for older people 300 years later.

ferguswilde

Thanks Peter – the views are rather fine, do you have them on the wall? Perhaps there’s something rather nice about the almshouses still being there after the great houses have gone. Some traditions are worth keeping.

Anthea Jones

This is a fascinating blog. Would it be relevant to suggest the Garden History Society might be interested? I am pursuing the Kip engravings of Gloucestershire houses, and Gloucestershire Archives has one of the volumes of Britannia Illustrata.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Anthea!

I’m glad you enjoyed the blog post. We’d be happy for the Garden History Society to know about the blog and our holdings of Britannia Illustrata – do you happen to know anyone there you could mention it to? It looks like none of us here is a garden historian.

Anthea Jones

Could double delivered mean folded in two?

Anthea Jones

Or on second thoughts, perhaps double delivered meant the engravings were printed on a double page – i.e. half on the reverse side of one sheet and half on the facing sheet.

ferguswilde

Hi Anthea, thanks for figuring this out! My reading of ‘… whereof 60 are finished, and the Subscription not being full, This is to give notice to all Lords and Gentlemen who have a mind to be concern’d, to come or send to the said Undertakers house in the corner of the Old Palace-yard, Westminster; next door to the steps that go up to the House of Lords. The Articles are: that a 100 subscribers shall pay £10 each. That every Subscriber shall have two prints of each impression, which makes in all 200, and shall have 60 prints double delivered.’ is that he has printed copies of 60 of the plates, but hasn’t enough subscribers. So he’ll try to get 100, and when he does, he’ll print and issue two copies of all the plates, and people will also get a delivery of the 60 he’d already done on top of the newly printed set – so you’ll end up with four prints of those 60. He obviously doesn’t think he can sell the 60 already run off separately and hopes the ‘double delivery’ will appeal a little to potential new subscribers.