- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- Belle Vue – search archives catalogue

- Digital Resources

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Prints and Photographs

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Blog

- Support us

Dame of Dialect

‘I have laboured in the field of Lancashire literature for over half my life-time, and have tried to bring forth the pure gold hidden beneath the surface of the people’s nature.’

M. R. Lahee 1891

We are very excited about our recent acquisition of works from the collection of the late Dr Eddie Cass, a great student and collector of all things Lancashire. Volumes by M. R. Lahee intrigued us as we started to unpack this treasure trove and wondered who this writer was. A portrait of a surprising and fascinating woman started to emerge from the ‘biographical’ section at the beginning of the thirty-third edition of her Owd Neddy Fitton’s Visit to the Earl o’ Derby. The library’s copy of William Pollard’s recently published biography, M.R.Lahee Rochdale’s Forgotten Dialect Author (2016), also provided a wealth of information about her life, the social and political contexts in Lancashire and Ireland alongside detailed descriptions of her prolific writings. We also learned from Pollard that she referred to Chethams in her story Owd Yem un his Foive Daughters:

‘Thur wor a rum skit abeawt it i th’ Blue Pits Chronicle a first rate commercial paper …. Aw had a copy or two on it misel but th’ yed chaps ov Cheetham’s College come o’er un borrow’d em fro me, un thet nare sent em back sin.’

Margaret Rebecca Lahee was a rare female author in the male dominated world of 19th century Lancashire dialect writing. She grew up in Ireland, where she was born in 1831, and moved to Rochdale as a young woman to learn millinery, dress and mantle making from a friend of her relatives, Miss Kavanagh. She did not take to stitching so decided to earn her living as a writer. She had landed in the right place as nineteenth century Rochdale was known for its dialect writers, and she was particularly inspired by the renowned local writer, Edwin Waugh.

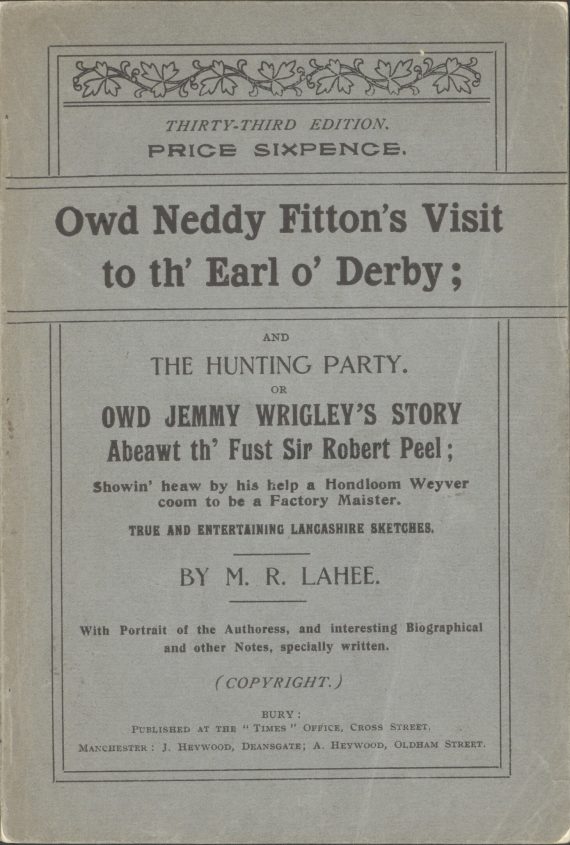

Her first publication, Owd Neddy Fitton’s Visit to the Earl o’ Derby, was based on the true story of Neddy Fitton who refused to accept a steep rent rise from his landlord’s agent when his lease came up for renewal. He insisted on putting his case in person to his landlord, The Earl of Derby, who was so taken with him that he renewed the lease without raising the rent. Owd Neddy was an immediate success and went into many editions. The biographical section of this book cites Edwin Waugh’s view of it as ‘the best story in the Lancashire dialect.’ William Dinsmore also regarded her as ‘one of best writers in the Lancashire vernacular’ in an appreciation he wrote for the Manchester Literary Club in 1895, Lancashire Novelists: Miss Lahee.

This success was a remarkable achievement for an Irish woman who had no knowledge of Lancashire dialect only a few years previously and who was writing in a very male dominated field at a time when there was significant anti Irish feeling. Pollard notes that she concealed that she was a woman and that she was Irish, initially by publishing anonymously, or using her initials, MRL, then later as the gender neutral M.R. Lahee.

Owd Neddy Fitton’s Visit to th’ earl o’ Derby cover

Like other dialect writing, Lahee’s work is peopled with quaint local characters based on the people she befriended in her neighbourhood and on her rambles round the local countryside. Her stories are drawn from the routines and events of their everyday lives and are written in standard English alongside the vernacular which she adopts to portray poor and working people. Modern readers can find Lancashire dialect very difficult to read, and looking at it through a contemporary lens can lead us to dismiss it as simplistic, whimsical, and patronising. However, it was extremely popular in its time, perhaps because it held a mirror to and affirmed the way of life, language, culture and humour that readers valued. As Lahee writes in her preface to Owd Neddy Fitton’s Visit to the Earl o’ Derby:

‘I ought perhaps to offer some apology for certain homely words which may appear coarse and vulgar to the more fastidious reader, but as NEDDY was nobbut a gradely straightforrad owd chap, an’ noan used to sich loike mee-maw wark as refined Literature, I thought it but justice to him to transcribe this tale in his own plain language, and I am of the opinion that the honest John Bull manner of the old Lancashire farmer will be admired throughout the work.’

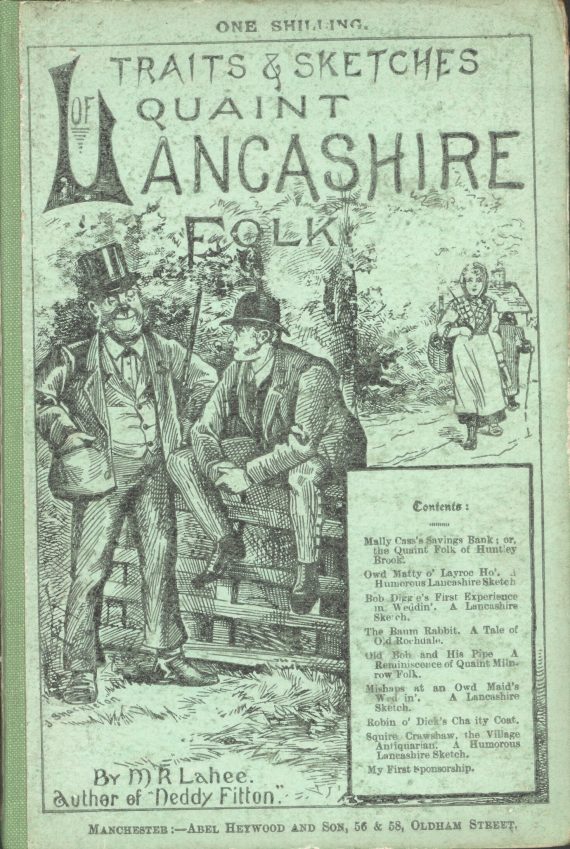

A perceptible difference between Lahee and her male contemporaries is that she presented the female perspective in relationships between women and men in her humorous stories. Her stories also brought out some of the particular difficulties women faced because of inequalities in their social, legal and financial circumstances. In Traits and Sketches of Quaint Lancashire Folk, published in 1887, she touches on women’s rights. Old Bob has just left the workhouse after leaving prison where he was sent for playing his pipe. He moans:

“Ay, folks talkin a deal abeawt women’s reets. I ownder what mak o’ reets thaem are, for us chapsha’ noan o’ no sort.”

“Noather han we Bob. But just wait til th’ women gett’n into Parliament, an’ then we’ll mak a justice o’ p’ace o’ th’ owd Almanac; hoo’ll mak a stunnin cheerman.”

Traits and Sketches of Quaint Lancashire Folk cover

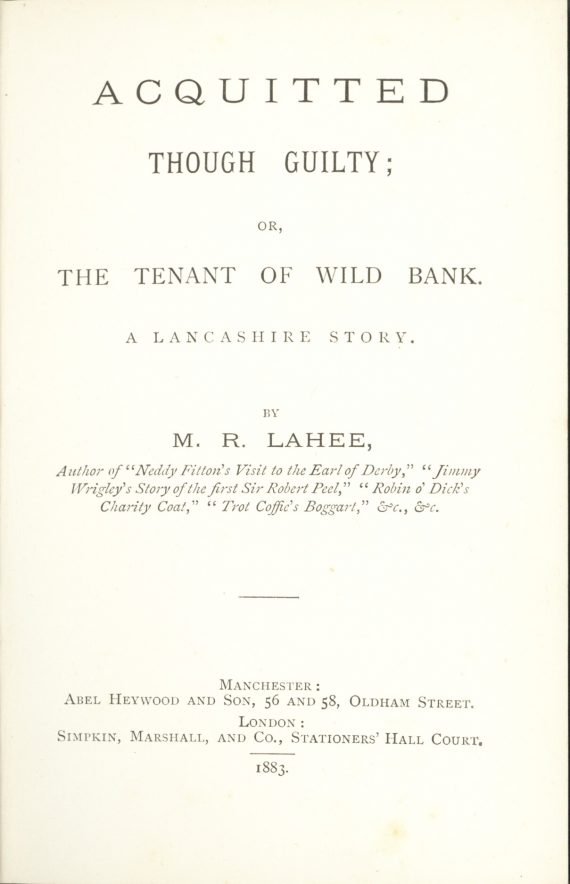

The library has copies of Lahee’s first novel Acquitted though Guilty (1883) and Sybil West written in 1893. Acquitted though Guilty is a rather sentimental and predictable story, but it does also address serious themes such as the financial vulnerability of widows, rural poverty, greedy landlords and unscrupulous agents. Sybil West (1892) tackles the working conditions of women mill workers, especially the pressures placed on women and their vulnerability to sexual assault.

Acquitted Though Guilty title page

M. R. Lahee’s personal life was unconventional and she was not universally accepted by Rochdale’s establishment. She lived in a close relationship with Susannah Rothwell Wild for over thirty years until her death in 1895. She requested they should share a grave and the inscription on the tombstone should read, ‘They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in death they were undivided.’ The local establishment, possibly instigated by Archdeacon Wilson, refused to meet her wish to be buried in Healy churchyard although it is not known whether this was because she was a woman, not from Rochdale or her sexuality. Wild died a year later and although she was buried in the same grave, it was never marked with the inscription she had wanted.

After Lahee’s death a public meeting in Rochdale Town Hall decided that a memorial to Rochdale dialect writers should be erected. Archdeacon Wilson opposed Lahee’s inclusion on the monument but Wild, who was devasted by Lahee’s death, successfully campaigned to make sure that she was one of the writers celebrated. Edward Sykes, a local architect, was commissioned to design the monument which was completed in 1900 and features portraits in bronze by John Cassidy of Margaret Rebecca Lahee, Oliver Ormerod, John Trafford Clegg and Edwin Waugh. We can still see the tribute to this remarkable woman on the memorial in Broadfield Park, Rochdale.

Dialect Writers Memorial Broadfield Park Rochdale

4 Comments

Maeve Fagan

I am secretary of the Lancashire Authors Association and we have several of Margaret Lahee’s books. One of our members knows of a story called The Carter’s Tale and has been looking for a copy. We do not have it and although it is mentioned on the website of Salamanca University’s database of English dialect they do not have a digital copy. Yours is the only other website I have been able to find that has mention of her works and I wonder if you have a copy of the story.

Eileen Earnshaw

Thank you for this essay on Margaret Lahee. Very interesting indeed.

I would like to read her work, is it available anywhere?

Mohammed Azhar

I read her poem about end of life and meeting the great God, as inscribed on the memorial.

It’s very sobering and inspirational. Reminded me of my mother, who toiled in the local cotton mills to raise me, after arriving from Pakistan in the 1960s as a penniless single mother of three children. RIP.

ferguswilde

Thank you, Mohammed. It’s good to hear you found her poem inspiring; mothers make so many sacrifices for us, and remembering them is good, though it can be painful.